Urban Design and Infrastructure in the modern era

A lesson in right-sizing, leveraging, and urban placemaking

As noted in books like Suburban Nation and Geography of Nowhere, since the end of World War II the United States set forth an endeavor never before imagined: The full scale adoption of the automobile and the re-engineering of much of the country in service solely to that mode of transportation. In the mid-20th century, these efforts led to the sorting of American cities into shadows of their former selves. Unbridled highway construction, and other infrastructure investments such as sewer systems, were prioritized, flooded with funding, and constructed with impunity. This unleashed development of land on the fringes of cities and in formerly rural areas. Existing city centers were demoted to being “Central Business Districts” – worthy of only a businessman’s daytime hours. Close-in neighborhoods transformed into zones merely to drive through, ultimately becoming the landing place for those who could not take part in the flight to the suburbs. As a way to breathe life into emptying cities, “Urban Renewal” projects promised a way to clean up what seemed to some as slums and blight. Highway projects, originally conceived of as ways to connect cities, were retooled to clear eyesores. My city, Cincinnati, was no exception. A Midwestern Story of Renewal

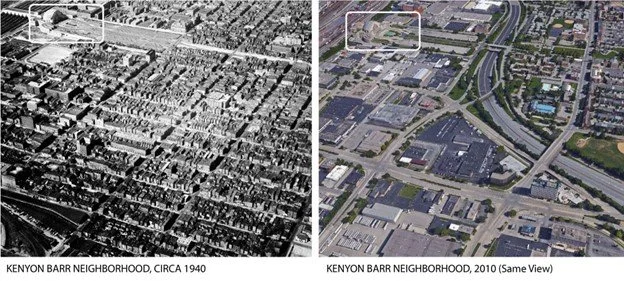

At the end of World War II, Cincinnati’s city fathers not only bullied a highway through our most economically fragile communities, they literally demolished neighborhoods where people of modest means had thrived – many of whom were people of color. In addition to highways, Cincinnati’s Urban Renewal led to the creation of a suburban style industrial office park built over the remains of a once dense urban neighborhood. The same happened on our riverfront. In all, more than 25,000 people were moved (Robert Moses Style) out of the Kenyon-Barr and West End neighborhoods and promised quality places to move to. This urban renewal operation took over a decade, from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s. The final pieces of this era were the construction of the new sports venues along the unappreciated Ohio River. “Riverfront Stadium” became the home of the Reds and newly created Bengals, and “Riverfront Coliseum” was erected to attract an NBA franchise. Of course, massive parking lots were built to accommodate all of the visitors. By 1974, all was complete. The mission of Urban Renewal had run its course – and run out of money. Similar stories could be told of other Midwestern cities: Pittsburgh, Buffalo, Cleveland, St. Louis, Minneapolis, and even Detroit. For an entire generation, these cities experienced population loss, business exodus, institutional decline, and the segregation of those ‘left behind’.Northern and Midwestern cities suffered a crisis of identity. Cincinnati, by its 1988 bicentennial, had dropped from one of the dozen most populated cities in the country to farther down the list; a middling position for a once proud city. The greater region, though growing, was largely doing so by cannibalizing the exodus from the city. True growth was meager. By the mid-1990s, the luster long gone from Cincinnati’s Urban Renewal Projects, the city was bleeding population and hemorrhaging pride. This identity crisis reached a crescendo with the threat that our beloved Bengals might pull up stakes and leave town, like the Colts had done to Baltimore and the Browns had done to Cleveland. Opportunity Revealed

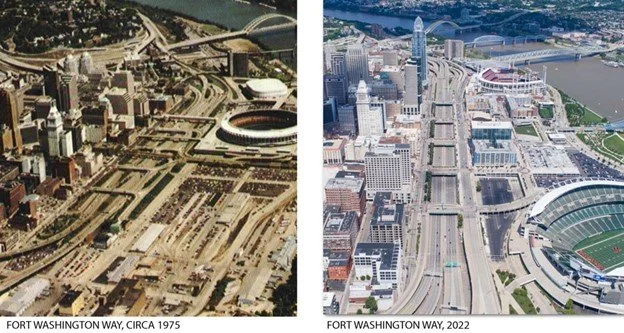

However, amid this identity crisis, several discrete elements came together to create a unique opportunity for the city:· The Bengals demanded a new, sole purpose home· The Reds wanted a new, baseball-friendly stadium · The DOT wanted to reconstruct a section of interstate highway which had long divided downtown from the Ohio RiverWith these imminent challenges swirling around, a few forward looking people took the chance to undo some of the damage of Urban Renewal and initiate a project rooted in the ideals of urban planning and placemaking. The efforts of these people exemplified many tenets of CNU. Instead of simply repaving a 1940s era immensely wide, divisive highway, they proposed compacting that roadway into a reasonable dimension, thereby leaving room for better stuff. A new, mixed-use district could be built, framed at each end by the new stadiums, and a resurrected city street grid could reconnect our downtown to the river that gave us birth. The idea sparked the imagination of a city that, for 200 years, had been proud of its heritage but now barely recognized itself. And while the State DOT was not interested in the plan at the beginning, the idea steadily grew until the CITY offered to take on the project as manager. The City built it the way they wanted: a narrowed highway (called Fort Washington Way), stadiums, street grid, a museum, a riverfront park, and more. The highway project that engineers first told city leaders would take a decade to design and build was, in fact, designed and completed in just 25 months. Development of the stadiums and mixed-use district took much longer.By 2015 (the year Cincinnati hosted the MLB All-Star Game), Cincinnati had a narrowed highway, two new stadiums, a new museum (the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center), hundreds of apartments, and dozens of restaurant and retail spaces – all in the land which had been linked to downtown by a reconnected street grid. The project is now called “The Banks”.Unlike the end of the Urban Renewal era, when the promise of those ideas seldom delivered, the Fort Washington Way and The Banks projects are just the beginning. Having overcome heated arguments about a highway project, the results prove that those who advocate for reducing highway footprints and reconnecting urban street grids are right. Combining infrastructure and urban planning can leverage productive development and till fertile ground for communities. For the first time since the 1950s, Cincinnati is gaining population. What’s Past is Prologue

The question repeats: do current leaders realize what led to the growing, vibrant city they have today? And will they, with that knowledge, invest in similar ways or will they acquiesce to ambitions for expansive urban highways again? Arguments are now underway regarding the Brent Spence Corridor project, and those of us who cherish the renaissance of our city hope our leaders will understand what is at stake. They have the power to insist on New Urbanist ideals which usher in the next great period of growth. Author Bio:

Brian Boland is a CNU Midwest Board Member and founder of Bridge Forward, the group advocating for a re-imagined Brent Spence Bridge project in Cincinnati, Ohio.